Another version of this post originally ran on Jewish Special Needs Education: Removing the Stumbling Block.

Do you know Jonathan Mooney? You need to. He’s awesome. He has been the opening keynote speaker for our Matan Institute for Congregational Educators and he has yet to disappoint. In fact, he just gets better and better.

Do you know Jonathan Mooney? You need to. He’s awesome. He has been the opening keynote speaker for our Matan Institute for Congregational Educators and he has yet to disappoint. In fact, he just gets better and better.

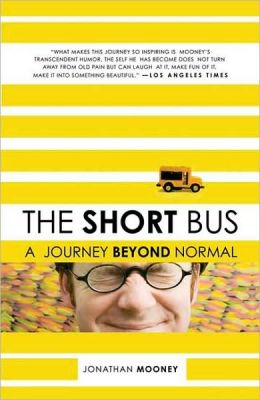

I recently read his book, “The Short Bus: A Journey Beyond Normal”. I was immediately drawn in by his deliberate use of the proverbial short bus. Instantly recognizable and virtually impossible to overcome as a stereotype, the “short bus” brings with it society’s negative constructs around special education and the derogatory slurs assigned to children who have disabilities. Whether you are as immersed in the world of inclusion as I am or not, this is a book of outstanding depth and profound insight.

I was most struck by chapter twelve, a chapter which focuses on Katie, a young woman with Down syndrome. As a part of his quest to understand “normal”, Mooney explores Katie’s desire to live an ordinary life, yet worries aloud that this may not be possible in America. In conversation with Katie’s mother, Mooney learns of her fear that Katie will always be poor as she “does not accept SSI or any other aid from the federal government…If Katie accepted SSI, she could earn no more than seventy dollars a month from a job; if she made more than that amount, she would lose SSI money. To remain eligible for Medicare in Ohio, Katie could accumulate no more than a thousand dollars’ worth of assets. So Katie can’t even own a cheap, used car. [Her family] had been told not to include Katie in their will, because this “wealth” would threaten her future ability to get SSI and Medicaid”. I think that one reason this may have resonated so deeply for me is that I spent time earlier this year in Washington DC lobbying on behalf of the ABLE Act as a part of Jewish Disability Advocacy Day. There are similar stories to Katie’s all over our country.

Further, as an advocate for inclusive education, I found it frustrating that “Katie’s space in the community college, one of her best outlets for socialization, was also evaporating. Because of a complicated legal loophole, she is not eligible to receive special accommodations in her classes without identifying herself as a student with a disability. But if she self-identifies as a student with Down syndrome, she will be considered ineligible for financial aid and accommodations because, based on an assumption of her “low IQ” she would be considered to have no “abilities to benefit” from higher education.”

And so, given all of this, Mooney earnestly asks Katie’s mother, “How do we help Katie?” By way of reply, she simply laughs. “I understand where that question comes from – I used to ask myself the same question. How can I help or fix Katie? But Katie isn’t the one who needs to be fixed.”

And there it is. There is the profound truth. When we spend our lives trying to “fix” our children and our students; no matter how pure our intentions, we perpetuate a societal concept of “normal” that views disability as broken. It is deep in our cultural consciousness to view Katie and other people with disabilities through the lens of what is wrong with them. We teach, we train, and we try our best to fix. But our children aren’t broken.

That’s it. It’s a simple truth. Our children aren’t broken.